Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy is a film

full of an immoral undercurrent, seething in filth but never becoming jammed

down by it; if anything, it is all the more compelling because of it. His adoration

for the underlayers of society lives on in his follow-up to his Academy

Award-winning masterpiece Precious.

That was a world devoid of innocence, and this is much the same.

Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy is a film

full of an immoral undercurrent, seething in filth but never becoming jammed

down by it; if anything, it is all the more compelling because of it. His adoration

for the underlayers of society lives on in his follow-up to his Academy

Award-winning masterpiece Precious.

That was a world devoid of innocence, and this is much the same.Saturday, January 5, 2013

The Paperboy

Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy is a film

full of an immoral undercurrent, seething in filth but never becoming jammed

down by it; if anything, it is all the more compelling because of it. His adoration

for the underlayers of society lives on in his follow-up to his Academy

Award-winning masterpiece Precious.

That was a world devoid of innocence, and this is much the same.

Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy is a film

full of an immoral undercurrent, seething in filth but never becoming jammed

down by it; if anything, it is all the more compelling because of it. His adoration

for the underlayers of society lives on in his follow-up to his Academy

Award-winning masterpiece Precious.

That was a world devoid of innocence, and this is much the same.Sunday, June 10, 2012

On the Road

In 2004, filmmaker Walter Salles brought to life the extraordinary travels of a young medical student named Ernesto Guevara in his stunning The Motorcycle Diaries. Flash forward eight years and Salles is doing the same again, taking the physical and philosophical journey of a young Jack Kerouac across North America and fashioning it for the screen in On The Road. An adaptation of Kerouac’s autobiographical novel, Salles could not have been a more perfect fit for the material, and the finished product is a stirring tale of a society changed forever; an amazingly crafted coming of age story which will no doubt remain as one of my favourite films of the year.

In 2004, filmmaker Walter Salles brought to life the extraordinary travels of a young medical student named Ernesto Guevara in his stunning The Motorcycle Diaries. Flash forward eight years and Salles is doing the same again, taking the physical and philosophical journey of a young Jack Kerouac across North America and fashioning it for the screen in On The Road. An adaptation of Kerouac’s autobiographical novel, Salles could not have been a more perfect fit for the material, and the finished product is a stirring tale of a society changed forever; an amazingly crafted coming of age story which will no doubt remain as one of my favourite films of the year.On the Road is the story of Sal Paradise (Sam Riley), a young man coping with the death of his father, a severe case of writer’s block and a burning desire to live with the mad and the crazy. He and his friend Carlos (Tom Sturridge) soon become intertwined with the life of a charming and beautiful ‘jailkid’ named Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund), who, along with his teenage wife Marylou ( Kristen Stewart), have made their way to New York. The troupe spend some months balancing the pressures of their banal days with the always eventful and often frantic nights on the town; Sal stands by in a haze of marijuana, Benzedrine, alcohol and sex, keeping a watchful eye over the others, always there but never becoming too involved. Yet these accomplices, especially Dean, will change his life forever. Soon the streets of New York become too familiar, and Carlos, Dean and Marylou leave Sal behind as they begin their journey to the west. His life without inspiration, Sal resolves to follow his friends, and so begins his journey on the road.

An ode to a time not so long passed, On the Road is excellence on all levels. As one could only expect from Salles, the road becomes so much more than simply the setting of this story, and the way he builds this journey in a cinematic sense illuminates Sal’s journey well. The hedonistic lives of Kerouac’s characters become so brilliantly alluring thanks to Salles, plotting each character's step along the expedition faultlessly. Reuniting with cinematographer Eric Gautier, the film illustrates the American road as a path of ferocious delight. Aurally, the film sends you back to another world, and it’s incredible to note the impact this has on the way one experiences the film; once again, Gustavo Santaolalla can be hailed as enhancing the impact of Salles’ film, the same way he did it for Salles’ Diaries. Jose Rivera’s screenplay also provides a failproof map upon which these character’s lives meticulously wander in and out of each other’s way, and he adapts the source material superbly.

And yet one would not be wrong in thinking this film is the perfect vehicle for a generation of careers to be built upon, and the casting here is particularly exceptional. Stewart is an absolute marvel; her Marylou is the quintessential runaway teen bride, and she portrays Marylou’s turbulent coming of age with considerable aplomb. Riley is a great choice for Sal, seamlessly underplaying the role and crafting a crystal clear eyepiece through which the audience can view the story of the Beat Generation in full brilliance. Hedlund is courageous in his candid portrayal of our young delinquent, lacing his performance with considerable allure. Kirsten Dunst and Sturridge are also effective in their somewhat smaller roles.

And yet one would not be wrong in thinking this film is the perfect vehicle for a generation of careers to be built upon, and the casting here is particularly exceptional. Stewart is an absolute marvel; her Marylou is the quintessential runaway teen bride, and she portrays Marylou’s turbulent coming of age with considerable aplomb. Riley is a great choice for Sal, seamlessly underplaying the role and crafting a crystal clear eyepiece through which the audience can view the story of the Beat Generation in full brilliance. Hedlund is courageous in his candid portrayal of our young delinquent, lacing his performance with considerable allure. Kirsten Dunst and Sturridge are also effective in their somewhat smaller roles.Though at times becoming slightly uneven and perhaps a tad long, On the Road is a tremendous cinematic achievement. Salles turns the character-driven novel into a visual spectacle, without ever compromising the journey (both externally and internally) of his characters. With mixed reviews at Cannes, one has to wonder whether the audience was exposed to the same whirlwind of psychedelic drugs that this story’s characters were, because, quite simply, the film is a marvel.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Beasts of the Southern Wild

Saturday, February 4, 2012

"Clarice, the world is more interesting with you in it."

In misty woods nearby

Historically, the sole female protagonist is an alien in the world of film, especially of the select few which have been honoured with film’s greatest prize; sure, there are plenty of examples of films where the female’s plight is so intricately combined with that of the male protagonist – we have to care about her then! – but, with the rare exception (Gone with the Wind, All About Eve, The Sound of Music), the lone female protagonist is so often neglected by Oscar. Here is another of those rare examples, a film which would be an enjoyable but fairly empty exercise if it were not for its extraordinary female lead.

Indeed, The Silence of the Lambs’ greatest accomplishment is found in its subtext, and Starling as a character is a rare gem, the perfect embodiment of that subtext. This is a film which relies so emphatically on the power of its female hero to grab its audience and allows her to explore so meticulously the position of the female in contemporary society.

The film centres on the investigation into a string of murders and the subsequent manhunt for the elusive serial killer known to the authorities as ‘Buffalo Bill’ – a nickname, we find out later, given to him because he likes to skin his humps. The FBI desperately wish to solve the murders and believe a psychopathic genius in custody has clues needed to crack the case; and yet, this incarcerated psychopath, Dr Hannibal ‘The Cannibal’ Lector (Anthony Hopkins) will not help. That is, until the FBI strategically dangle the perfect bait in front of him: the furiously determined, highly intelligent and yet incredibly precarious Starling (Jodie Foster).

Director Jonathan Demme’s love for Starling is unwavering; it’s clear she has significant hurdles to overcome in the pursuit for success and he emphasises this seamlessly. She (both literally and figuratively) runs in another direction to her colleagues in the male-dominated Bureau; where they succeed in one arena, she will make her mark in another. The relationship she shares with her mentor is particularly indicative of her solitary quality; their interaction is marked by Starling’s wariness from the start, and as her importance in the investigation heightens, she (appropriately) reprimands him for his chauvinistic handling of her. Other male contemporaries look at her in a sexually degrading manner; she is the foreign, the unknown and, in many ways, the unwanted. Oddly enough, the exception to this rule is her dealings with Lector; he is respectful, courteous, endearing. This is why their interactions are by far the most absorbing of the piece: he is the only one allowed to be her equal.

Yet Starling’s finest moments are not those where she proves herself to be an exemplary agent-in-training; instead, it is when the audience are allowed to see her vulnerability. Demme and especially Foster offer Starling as an incredibly exposed hero, and though she is in many ways extremely brilliant, she is also broken. Lector exposes Starling in a way no other character does in this piece, and their interactions are captivating and incredibly electric. Their rapport is like no other; Lector, a sociopathic killer, shows no regard for human life, though in spite of this there exists incredible awareness and care for Starling, and she is equally as captivated by him. Their exchanges are wonderfully well-written, witty and brutally honest, and in this, Ted Tally succeeds like no other. Once you add Foster’s incredible depth and

Perhaps the most ironic thing about the reputation of this film is that it almost always centres on

Thomas Harris’ source material for this film can at times be incredibly dry and to-the-point, the subtext, while existing, is sometimes clandestine, and the novel itself is quite cold. Tally’s adaptation brilliantly fills in these flaws; his characters are far richer, the subtext is elucidated better without ever becoming obtrusive and the plot is better assembled. While staying true to the novel, he literally recreates Harris’ novel in a much denser fashion, and it shows. Demme flawlessly assembles all these brilliant pieces together in such a wonderfully complimentary fashion; his helming of this piece is an absolute wonder and he balances each element perfectly.

In the words of a wise woman, “it can be about the performance and not the politics”. This was a film released in February by a soon-to-be bankrupt production company. It is a dark, often brutal crime thriller with horror-like elements (it was the first, and remains the only film that can be considered ‘horror’ to win Best Picture – though whether it sits comfortably in that genre is something else worth considering). And yet here we are, twenty years later, discussing its incredible and utterly worthy win. It seems it was just too good to ignore.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

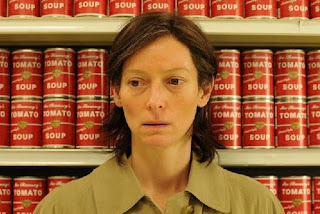

Talking about Kevin (and Tilda Swinton)

It's not that Swinton's Eva isn't a worthy performance - quite the opposite in fact - but Kevin is confronting, draining and in many ways controversial. Given that the film is an adaptation of Lionel Shriver's award winning 2003 novel by the same name, the film was always going to attract some attention; it was inevitably going to have a much bigger profile in the US than either of Swinton's previous two films. The material (as anyone who read the novel should know) is heavy, quite often troubling the reader with difficult and somewhat taboo ideas to reconcile in one's own mind, and Kevin's director, Lynne Ramsey, certainly doesn't shy away from delivering the novel's key themes. Despite adapting the source material in such a way as to remove the key devices which Shriver uses to tell her story (the novel being written in a first person epistolary format), the film never sacrifices the heart of the story and always stays true to its main character.

It's not that Swinton's Eva isn't a worthy performance - quite the opposite in fact - but Kevin is confronting, draining and in many ways controversial. Given that the film is an adaptation of Lionel Shriver's award winning 2003 novel by the same name, the film was always going to attract some attention; it was inevitably going to have a much bigger profile in the US than either of Swinton's previous two films. The material (as anyone who read the novel should know) is heavy, quite often troubling the reader with difficult and somewhat taboo ideas to reconcile in one's own mind, and Kevin's director, Lynne Ramsey, certainly doesn't shy away from delivering the novel's key themes. Despite adapting the source material in such a way as to remove the key devices which Shriver uses to tell her story (the novel being written in a first person epistolary format), the film never sacrifices the heart of the story and always stays true to its main character.Ramsey's visual mind is utilised effectively so as to translate these troubling and concerning literary elements of the novel into a visual feast; the film's opening scene, a sprawling, tomato-stained holy orgy is a foreboding entrance to Eva's story, setting the tone well for what is about to come. The film's scattered narrative may present difficulty for some, but for me it was the perfect way to understand our lead character's troubled mind; Ramsey's vision perfectly encapsulates the heavy weight on Eva's present as well as the contained trials of Eva's past, reconciling the two in tantalising agony. Throughout, violent flashes of the story's devastating climax are blasted to warn us of what is to come, and it is much a case of the audience not being able to take its eyes off the catharsis as it speedily approaches.

And yet Ramsey's greatest asset is her leading lady. Swinton is the perfect embodiment of the lead character, personifying every ordeal within to externalise a mother the audience can empathise with despite the very troubling sentiments we are left to digest. In those scenes from the past, there is a pain Eva tries to offload, and Swinton effectively shares that burden with the audience; yet in Eva’s present, an affliction even heavier remains centralised within, exposed only in a glazed emptiness behind Swinton’s eyes and the lethargy with which she staggers from place to place. Swinton’s masterful understanding of her craft allows the audience into Eva’s world, a place few would dare enter but one which Eva traps herself within. Swinton understands Eva’s plight like so few actresses could, every masochistic motion is undertaken with such subtle yet powerful emotion and her eyes are the most vivid of vessels which the audience can take this journey on.

This performance is one of the greatest I have seen in some time,

certainly the best of Swinton’s career. Her empathic delivery of one of the most difficult character arcs I have seen in some time is a testament to her extremely well refined talent as well as effective directing from Ramsey. Putting together this piece in such a commanding yet controlled manner allows Swinton’s underlying appreciation of Eva’s plight to shine through. The pair’s powerful chemistry is the glue in this amazingly well-assembled adaptation, truly making the experience of Kevin precious, if difficult at times.

certainly the best of Swinton’s career. Her empathic delivery of one of the most difficult character arcs I have seen in some time is a testament to her extremely well refined talent as well as effective directing from Ramsey. Putting together this piece in such a commanding yet controlled manner allows Swinton’s underlying appreciation of Eva’s plight to shine through. The pair’s powerful chemistry is the glue in this amazingly well-assembled adaptation, truly making the experience of Kevin precious, if difficult at times.Friday, June 17, 2011

Martha Marcy May Marlene

she should definitely have the young ingenue spot in the Lead Actress line-up at next year's Oscar ceremony.

she should definitely have the young ingenue spot in the Lead Actress line-up at next year's Oscar ceremony.John Hawkes is also menacing; it's not as large a character as I would've liked, but nonetheless every moment he has, he is just enchanting. It's considerably more enticing than his Oscar-nominated performance in Winter's Bone (which I also enjoyed), frightening at times, charismatic at others. His role really doesn't get substantiated upon too much (which is probably the most disappointing aspect of the whole film) but with everything he has, it's a fantastic performance and hopefully one which will get him a few more supporting actor nods this year.

Overall, the film is extremely intense and thoroughly exploratory, though lacking any major release of tension. Durkin shows what a great ability he has, though the film does lack in some areas. Still, Olsen is wonderful and devastating, Hawkes is powerful and all-in-all, it's a thoroughly insightful, intriguing story. Although the film itself probably isn't going to be end-of-year-best level, Olsen certainly should be, and it's great to see such incredible talent at work.

The Tree of Life

clearly has some lofty aspirations, trying to depict the creation of the world and then attempting to give a sort of pseudo-philosophical discourse on creationism and evolution and life and such. It is clearly a thing of beauty; the visuals are amazing, the sequence of shots depicting the Big Bang and the beginnings of the Earth and the solar system are incredible, the score behind it is awesome, and together they are powerful, if slightly prolonged. Even the later scenes in the suburban and city environments are, if nothing else, well shot.

clearly has some lofty aspirations, trying to depict the creation of the world and then attempting to give a sort of pseudo-philosophical discourse on creationism and evolution and life and such. It is clearly a thing of beauty; the visuals are amazing, the sequence of shots depicting the Big Bang and the beginnings of the Earth and the solar system are incredible, the score behind it is awesome, and together they are powerful, if slightly prolonged. Even the later scenes in the suburban and city environments are, if nothing else, well shot.However, the compliments end here. The film itself is extremely tedious; the lack of direction in terms of plot may itself be very typical of Malick, but I think in this film it is very much to the detriment of the whole thing. There are three main sequences to the film: those depicting the creation of the universe, those with the family and those with Sean Penn's character lamenting on his past. Very little ties these together; the whole thing feels extremely disjointed, awkward and perplexing.

There is some depth in the narrative surrounding the family and ultimately the greatest disappointment for me was the real lack of precision in this narrative because there was clearly a great potential for this storyline. Pitt is quite good, Chastain is wonderful and the children do great jobs as well, especially the portrayal of the young Jack, by Hunter McCracken. In fact, McCracken's exploration of the identity of Jack is probably the real highlight of the film. Unfortunately, this exploration suffers because the audience's attention is constantly being drawn from Jack and onto Pitt's character, who is, for the most part, impenetrable (and that is no fault of Pitt's). There is a nice moment towards the end of the film which does allow us some insight into Pitt's character, but that insight is so fleeting, it does little to rectify the last two hours of suffering.

Then we are thrown into a sequence of shots starring Sean Penn, who really has little to do except to look empty and depressed. The latter part of his sequence is almost Bergman-esque,

Seventh Sealstyle, which, although entirely pretentious, are almost fitting given that this film has pretty much been driving along on its last wheel for almost the entirety of its duration.

Seventh Sealstyle, which, although entirely pretentious, are almost fitting given that this film has pretty much been driving along on its last wheel for almost the entirety of its duration.I'm sure fans of Malick will enjoy this, despite it certainly being far from his finest hour. The whole thing is adventurous, wrought with danger and intrigue. It certainly had grand aspirations. But it fails, quite spectacularly in my opinion. I'm sure many are bound to disagree, but for me, this is easily one film I would have been very happy not to see.